“The only thing I’ve got is this film, man. This film is everything.

All these negatives - you see, there are thousands of negatives.

And there’s more boxes, at least 4 more boxes of negatives in this house.

Then there’s at least 3 boxes of nothing but slides. Color slides.

I’m afraid of what’s gonna happen. ‘Cause my immediate family - ‘Oh, these pictures is the devil’s work.’

But it’s not ‘the devils work.’ It’s the story. It’s my life, my story, and the story of people I’ve met and my friends.

So yes, I’m gonna try and print this shit.

- Alvin Baltrop, December 21st, 2002

Alvin’s initial artistic inspiration was his older brother James’ drawings - the camera was his own choice. He started in 1965 by asking male and female friends to pose nude. “I had got my first camera, a twin-lens Yashica. And I was out with my camera photographing everything. And then the summer after that, I saved up and I bought my first true 35mm: a Leica M3. I paid for that motherfucker every week. Every time I got an extra buck, I ran down there and put it down.

And my family was shocked. My brother said, ‘You spent all that money?’ And it was a lot for a kid back then, you know. And I said, ‘Yeah, I wanted this camera because it was the best.’ He said, ‘Yeah I know, I just didn’t think you were capable of it.’”[1]

“I’ve learned photography from some unusual people, old photographers who are dead now, who’d say, ‘bring your camera, kid, and we’ll go out shooting.’”[2] Another form of instruction was repeatedly visiting The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where Alvin studied vintage photographic prints for hours. For many practitioners at the time, photography was a loner’s art form. Individuals who were more than comfortable with being by themselves used their spare time to seek and document noteworthy faces, places and events, then spent hours in further isolation attempting to create the perfect print, the definitive visual record of the perfect image (or hopefully images) recorded during that day.

The razor-sharp wit and considerable charm which caused friends to immediately drop their clothes for his camera went dormant during the hours of intense focus and concentration which Alvin utilized in developing and printing. The darkroom was like a red-lit, single occupancy church one constructed for oneself within the porcelain-walled confines of a bathroom. The quiet, deeply meditative atmosphere was alternately obsessive - when reprinting the same image until the perfect print was at last achieved - and experimental - when seeking and discovering new ways to process and frame images. Underlying all of the creative fundamentals was the rush of excitement that resulted from finally striking the finished print of the scene that initially inspired the photographer to click the shutter.

The anti-establishment counterculture of the 1960s simultaneously invigorated Alvin, influenced how he utilized his time, and shaped what he chose to record with his cameras. The Yashica and Leica M3 documented the teenage Baltrop’s travels to Harlem where he attended civil rights rallies; to Lower Manhattan where he watched performances at The Living Theater (Frankenstein was a favorite) and The Performance Group (Dionysus in 69); to the Stonewall Bar and Inn, and to various bookstores to purchase publications by City Lights Books and Grove Press. Alvin was also lured by the three M’s which the counterculture had to offer: meditation, Marxism, and marijuana.

So much film was processed in the Baltrop family bathroom on Teller Avenue in The Bronx that the wallpaper began to yellow, buckle and peel. After Ms. Baltrop complained, Alvin spent an entire afternoon re-papering the walls, then promptly resumed developing and printing.

In 1969, Alvin was drafted and served in United States Navy. “I was just being sent to boot camp when they had the riots at Stonewall. My friends were sending clippings about it. We all used to hang out there, and now I was seeing my friends in the newspaper. I couldn’t tell anyone about it, but after my first year in the Navy I learned that I could be a whole person.”[3]

If Baltrop wasn’t drafted, he would have been in the streets rabidly photographing the rioters. Not being able to do so had a considerable affect on him. Although not physically present, he was there at least in spirit. For Alvin, in the immediate wake of the Stonewall Riots, the word “gay” had attained a strong anti-establishment stance that paralleled perfectly with his sensibility and political views at the time. Although he had relationships with men, women, transgender and intersex individuals throughout his life, Alvin preferred to use the word “gay” as it was a multifaceted term which encompassed more to him than mere sexual preference.

Alvin was very selective and specific in his use of language. Although he served in the military during the Vietnam War, he always referred to himself as a “Vietnam-era veteran” as he never traveled to Vietnam, and did not engage in combat. The word “bisexual” never appealed to him because it only referenced sexual tastes. In the Summer of 1969, “gay” had a revolutionary backbone, a foundation based on social dissent and a successful push against an oppressive authority. This fit perfectly in line with someone who, after participating in the March on Washington in 1963, was inspired to first attend, and later photograph civil rights-related events on his return to New York.

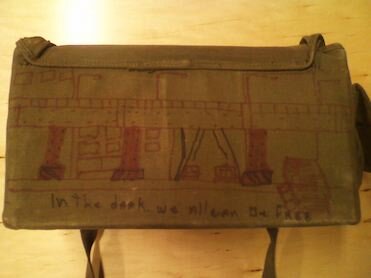

While at boot camp, Alvin considered the cultural changes his home city was going through, and how he would photograph this new New York upon his return. With red and black markers, he illustrated his thought process on a military-issue shoulder bag that housed his cameras. Below a drawing of Manhattan’s West Side Highway, he wrote the caption, “In the dark, we all can be free.”

“The dark” referred to the specific aesthetic and thematic qualities that Alvin was drawn to and which satisfied his particular sensibility, tastes and interests. Consider his description of his locker while in the Navy -

“On one door, I had a picture of Yukio Mishima. The Japanese author, film director who committed suicide. He had his head cut off, and he was gay. There was a famous picture of him doing Sebastian. He fell in love, when he was young with Sebastian, the Saint. And he modeled himself in many respects after Sebastian.

I had a picture of the man (a photograph by Max Waldman from Peter Weiss’ play Marat/Sade) tied up in rags in the insane asylum from that period of time. A scary-looking, dude, his eyes were bugged out, and he was drooling at the mouth, and I had these pictures on the wall. And the nudes of Mishima, with the Japanese sword, the headband and sweat dripping off of his nipples and everything, I had these nudes on my locker. Then when you opened the head section, where my head was, I had that photo and my books on the top shelf was Chairman Mao's The Red Book, and about 5 or 6 other books about Communism and Socialism. Then I had my collection of black magic books. Then I had my collection of switchblade knives. They asked, they wanted to know if I was insane.

Now I had drew mandalas, and different emblems and symbols for concentrating, 'cause at the time, I was into meditation quite heavily. So I would draw mandalas, and round emblems and all these little fancy things and I would put these up all the wall and I'd show kids how to meditate.”[4]

Due to his leanings and interests, “Big Al” earned another nickname not based on his looming height and stocky physique. “I was a medic. They called me W.D. - witch doctor.”[5] Being distanced from military confrontations gave Alvin the time and opportunity to concentrate on various photographic processes. “I built my developing trays out of medic trays in sick bay; I built my own enlarger. I took notes about exposures, practiced techniques and just kept going. I think I perfected my lighting skills. Later, working in a commercial photography studio I learned timing and how to frame a photograph in your head.”[6] The sick bay also served as a photo studio, where Alvin shot portraits and nudes of crew members.

In 1972, Alvin received an Honorable Discharge and returned to his family’s home in The Bronx. Not only was his beloved - and extremely expensive - Leica stolen while he was in the Navy, his mother had thrown away nearly all of his photographs due to her religious and political views. In short, the nudes were considered to be obscene, and although Ms. Baltrop was proud to have been with her sons to hear Martin Luther King Jr speak at the March on Washington, Malcolm X and the Black Panthers fell into her generalized category of “dangerous people”.

Alvin resumed documenting his life and all that his city had to offer. He began with photographing The Temptations, The Four Tops and other popular music groups at concerts in Central Park and Wollman Memorial Skating Rink with a small collective called “The Camera People”. As the younger Baltrop created new bodies of work, James’ art earned him inclusion in a group exhibition of prints and drawings at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1972. James’ work would eventually be featured in another show dedicated to bookbinding at the Museum in 1974. The Baltrop brothers paired up to sketch and shoot dance classes and performances in Harlem. When working alone, Alvin photographed friends, pedestrians encountered on the street, various locations throughout New York, abstract still lifes, and shot a series of intimate portraits and nudes of female street prostitutes in The Bronx.

Alvin never threw away any test prints that did not turn out as intended, preferring to crop them with X-Acto blades into smaller images or layered, 3-dimensional collages; perhaps this was a protective instinct instilled by his mother’s photographic purge. As he created new bodies of work to replace what was destroyed, Alvin entered an experimental period, frequently trimming prints into square and oblong shapes, the latter showing the influence of wide-screen black-and-white samurai films such as Kihachi Okamoto’s Sword of Doom (1966). The appreciation for the cinematography in these movies and the photographs of Yukio Mishima by Shinoyama Kishin and Eikoh Hosoe that adorned the former medic’s naval locker led him to the Museum of Modern Art in the spring of 1974 to see the exhibition New Japanese Photography, and to acquire the show’s catalog.

The impact that the MoMA show had on Alvin’s aesthetic can be seen in his important transitional work Untitled Portfolio (1972-1975), a collection of 27 photographs mounted on board. Alvin replicated the look of certain prints in New Japanese Photography by intentionally overexposing a few of his own prints to create harsh highlights, pitch black shadows and grainy textures. In addition to the MoMA exhibition catalog, Alvin’s copy of Waldman on Theatre (1970), a collection of Max Wadman’s black-and-white photographs of theatrical performances, was another source of inspiration.

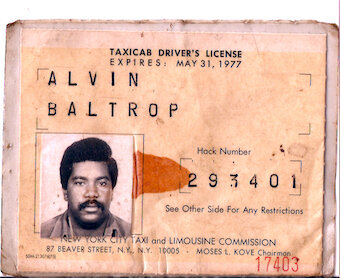

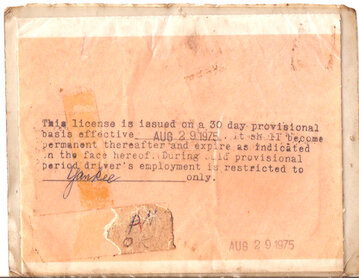

After using his G.I. bill benefits to study photography at the School of Visual Arts in 1973, Alvin stopped attending in 1975 as he could no longer juggle classes, working, and his own escalating photographic practice. In the same year he abandoned art school, Alvin began working as a taxi driver. While on his breaks, he used a police radio to get the locations of fresh crime scenes that he photographed. It was on these excursions that he started to shoot Manhattan’s West Side piers - a series of warehouses running from 59th Street to Tribeca, abandoned in the 1960s as the city’s shipping industry closed and moved to New Jersey.

Alvin’s initial interest in shooting activity at the piers was voyeuristic - the warehouses were a cruising area for gay men. In exploring the crumbling buildings on the waterfront, he saw the elements of a larger story and the makings of a photographic essay with vast potential. Alvin captured crimes in progress (an arsonist fleeing down a ladder after setting fire to one of the warehouses) and their stomach-churning aftermath; partial and intact corpses that surfaced along the waters at the edge of the piers for several years. “I'd walk into a room taking pictures and there'd be two guys with 2 x 4s, beating a kid, and I'd jump on them. I've gotten jumped by six guys at one time who tried to poke out my eyes. One day I fell through the floor and I was hanging there for a half hour before some guys helped me up. The piers were more than an institution. You learned.”[7]

While some freely went to and from the piers, others migrated there because they had nowhere else to go. The waterfront’s decaying buildings were a refuge and a haven for teenagers and young adults who were either kicked out of their homes by their parents or ran away because they were gay or transgender. “At one point the piers were full of kids who had been thrown out.”[8]

In 1975, Alvin met Alice, a fellow taxi driver who had a major impact on his life and photographic practice. “I think about Alice every so often. I did have a heavy love for her.”[9] “(Alice) saw what I was doing and urged me to shoot just the piers. I was afraid in the beginning and she helped me to not be afraid. She was always on me to do better.”[10]

Alvin and Alice moved into a 3-bedroom apartment at 89 East 2nd Street for $110 a month; this would be Baltrop’s home until his death in 2004. With a new relationship and residential address, Alvin settled into the bohemian artistic lifestyle he desired since the mid-1960s, working when he could to finance his photography. Additional funding came through selling cocaine while working part time as a bouncer at The Bar, an establishment formerly on the corner of East 4th Street. “I was making off the books selling coke, ten thousand a week.”[11] “At least it's something, and that's my attitude about it. Hey, it pays the rent, I pay the telephone bill, and I keep fucking going. I feel happy on a certain level.”[12]

“In my head, to be where I want to be, I have to put my money into that camera, and into that addiction. That camera is blood, and the film that goes in there is like plasma in many respects. And when you pull that shit out, you've got to do some heavy separating to separate the blood, the plasma, and your own personal soul to show it. And if you don't put your energy there, I mean really put your energy there, you ain't gonna turn out shit. So rather than turn out just plain shit, I don't shoot.”[13]

After buying a 1974 Dodge B100 van, Alvin obtained freelance work as a moving man which gave him more freedom and time to devote to his photography. “I had just got a van, and I’d spend days, nights, weekends at the river, with my van set up like a little house.”[14] During these excursions, there were frequent trips to payphones to check his answering machine messages for any potential moving jobs. After shooting for days, Baltrop returned to his apartment where he processed film in the bathroom for hours, sometimes falling asleep while standing up with his hands immersed in the developing trays. “I did it because I liked to do it. I liked the photography that I was doing. I liked what I was shooting. I wanted to get a good record, as much as I could, of what was happening at that period of time, so I was photographing everything.”[15]

Alvin’s drawing of the West Side Highway on his camera bag was realized in many photographs during this period. At the Highway, adjacent to the piers, he documented various prostitutes - women, men in drag and transgender - moving in and out of vehicles from customer to customer. The Highway is also visible in the background of photographs shot inside the pier warehouses. When not traveling in his van, Alvin journeyed on foot throughout New York, taking certain portraits of passerby who were unaware of the camera concealed in another shoulder bag he crafted specifically for clandestine shooting. Baltrop referred to this technique as “Practicing Invisibility”. “I’m always on the outside looking in. You shut your mouth and you disappear. Practice invisibility, and you’ll get the best shots. Who stares at a black man with a bag in his hand?”[16]

Although the quality of Baltrop’s work earned him a solo exhibition of pier photographs at Tribeca’s The Glines art gallery in 1977, the majority of institutions he approached were uninterested, some offering hostile reactions. “I don’t show my work too often because I get such an evil response. One woman said, ‘As I turn the pages of your portfolio, I can honestly say I’m afraid of your portfolio.’ And I said, ‘Why?’ And she said, ‘Because I am afraid to see my husband or my son pop up in one of your photographs.’ She said, ‘You must be a real sewer rat that you crawl around at night and photograph things like this. So I have to consider you a real sewer rat type of person and I’m not sure I like you.’ I closed my book and walked out.”[17]

“I used to be offended by the terminology of saying, 'I'm an artist'. I would say, 'Hey, I'm just a person who digs certain things and the photographs I like are for me and not for nobody else.’”[18]

Due to this widespread disinterest and disgust, Alvin’s artistic output eventually exceeded his financial ability to print the majority of what he shot, resulting in a collection of images that only existed on thousands of negatives which he hoped to have enough capital to print in the future.

Shortly after Alvin’s relationship with Alice ended in 1980, he became involved with Mark, who would be his partner for 16 years. Alvin obtained steady employment in Manhattan as a printing press operator, where he also processed film in dark rooms, maintained and repaired printing equipment, and oversaw the production and distribution of trade publications and marketing materials.

In 1985, Manhattan’s sex clubs were shut down by New York’s Department of Health to curb the spread of the AIDS epidemic. In 1986, the piers were destroyed with dynamite and leveled with bulldozers with the same intention. Alvin picked up his cameras and documented this destruction, excited to have a coda for the photographic essay he had worked on for just over a decade.

In 1988, James and Alvin started Baltrop & Baltrop, a commercial venture which sold reproductions of their artworks as notecards and pins at various festivals in New York, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Washington, and Detroit. Since childhood, the Baltrop brothers collected international postage stamps which they laminated and converted into wearable merchandise as pins.

As the ‘80s moved into the ‘90s, many of Alvin’s friends lost their lives due to AIDS. One of the first was Alice, who temporarily moved back in with him so that he could care for her. Before the 1990s concluded, Alvin’s losses included not only Alice, Mark and many other friends and companions but his mother and brother as well. Although intensely proud of his photography, the pictures sometimes became a source of pain. “I'm to the point where I don't even like to look at these photographs a lot of the time because there's too many stories involved with them. You understand what I'm saying? There are so many stories.”[19]

“I feel bad because, I can go in there, and I can pull out a textbook of photos of their departed son. And I’d like to do that with a lot of people, but, a lot of people don’t know anything about their children. And my photographs tell too many stories about these kids.”[20]

In the 1990s, Alvin encountered a new generation of displaced gay, lesbian and transgender runaways who were ostracized by their families and living on the streets as the piers no longer existed to house them. Using his skills and expertise as a medic and hospital corpsman, Alvin sought out and helped those pushed toward the fringes of society by offering recommendations for over the counter prescriptions, handing out condoms and delivering general life advice. He discussed wanting to buy land and building a compound where he would devote his twilight years to teaching photography to the outcasts he encountered.

Toward the end of the 1990s, complications from diabetes and cancer began to slow Alvin’s productivity and limit his mobility. After years of being under the radar, interest in the Baltrop photographs began to trickle in, resulting in inclusions in small group exhibitions and a nomination for the Louis Comfort Tiffany Award in 2003. Alvin discussed wanting to create new bodies of work in a return to photographing street prostitutes in Lower Manhattan at night with high speed film while concealed in a van, and experimenting with using handmade papers coated with clay and other unusual materials to produce inkjet prints. He also mused about restarting Baltrop & Baltrop and expanding the line of products to include other forms of retail merchandise based on his own and his brother’s art.

In September 2003, Alvin received poor medical care at a Veteran's hospital that led to a partial amputation of his foot. His concurrent health conditions were worsened after the amputation, resulting in his death on February 1st, 2004. Alvin shot his final photographs at the various hospitals and hospices he stayed in. Although Andy Warhol and Alvin Baltrop were galaxies apart in terms of financial wealth, both men died after receiving minor operations that absolutely should not have taken their lives.

“All I want to do is keep a history of what I saw as a black, gay photographer. Things that I desired, that I enjoyed. And people say, ‘Well, what does that mean to anybody?’ I say, ‘That means a lot to a lot of people.’”[21]

“I can tell a whole story and I try to tell my whole feelings - the touch, the smell and feelings. All I'm afraid of now is being like a few other guys I know who took photographs. When they die, maybe the family comes in and sees all this work they can't do anything with, and they just shove it into the garbage. I want people to see these photographs and say ‘this is something from my time.’”[22]

Copyright 2021 Randal Wilcox

[1] Interview with author, December 21st, 2002

[2] Hirsh, David, Native Night Out, Gallery Review, “Piers: Alvin Baltrop”, The Bar, 2nd Ave at 4th St, April 17-May 8”, New York Native, May 11, 1992

[3] Ibid

[4] Audio recording by Alvin Baltrop, n.d.

[5] Hirsh, op cit.

[6] Hirsh, op cit.

[7] Hirsh, op cit.

[8] Hirsh, op cit.

[9] Interview with author, Winter 2003

[10] Hirsh, op cit.

[11] Interview with author, December 21st, 2002

[12] Audio recording by Alvin Baltrop, 1977

[13] Audio recording by Alvin Baltrop, 1982

[14] Hirsh, op cit.

[15] Interview with author, Fall 2003

[16] Interview with author, Spring 2003

[17] Interview with author, Spring 2003

[18] Audio recording by Alvin Baltrop, n.d.

[19] Audio recording by Alvin Baltrop, early 1990s

[20] Interview with author, December 21st, 2002

[21] Ibid.

[22] Hirsh, op cit.